How the Myth of Objectivity Accelerates Modern Decadence

Belief in objective values has laid the foundations for mediocrity. So where do we go from here?

Never has originality been more aggressively pursued than in modern times. Yet, by esteeming this as a value above all craft and virtuosity, it has plunged not only art, but the whole of culture into the depths of mediocrity.

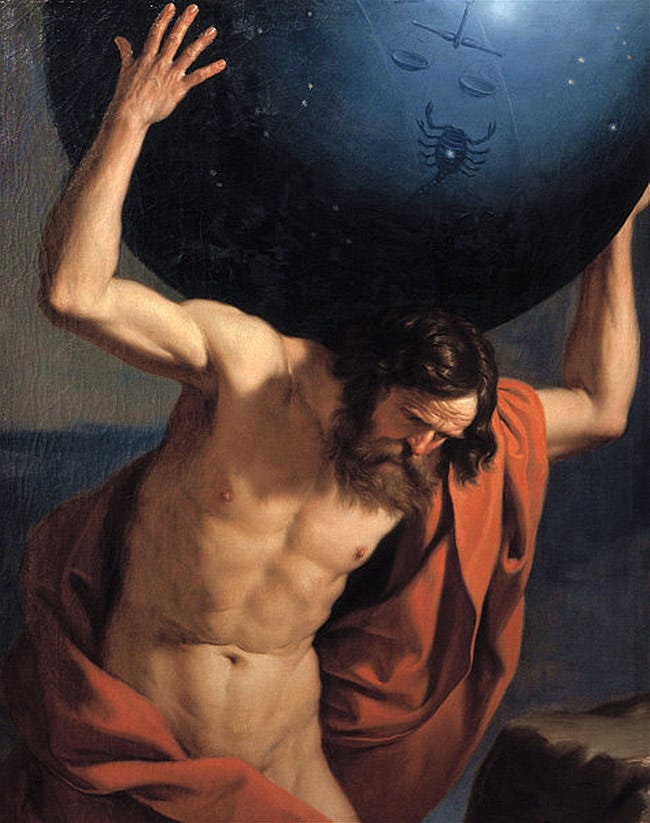

The modern attitude posits that all unique things are intrinsically worth more by their uniqueness alone. It fails to recognise that the principle of scarcity is born out of practical realities, rather than an end in itself. Not only this, but the proof of work—which ensures nothing can be produced without meeting established standards—has been altogether abandoned. No wonder that civilisation bows with too much weight, and the nausea of disequilibrium has become a daily struggle.

In past ages there was a systemically enforced penalty for abandoning the fundamentals of a given craft. Artisans of cultural works were supported by wealthy patrons, required to be both masters of technique and rhetoric. All accidents risked undermining the work’s intended effect. Therefore, an artist would undergo a high standard of training, first as learner, then apprentice, and finally as the face of the works.

There were also secondary layers of moderation enforced through institutions such as art academies. For example, the Académie des Beaux-Arts, using their monopoly on the public’s attention, were able to boycott any artist who did not adhere to the preordained standards.

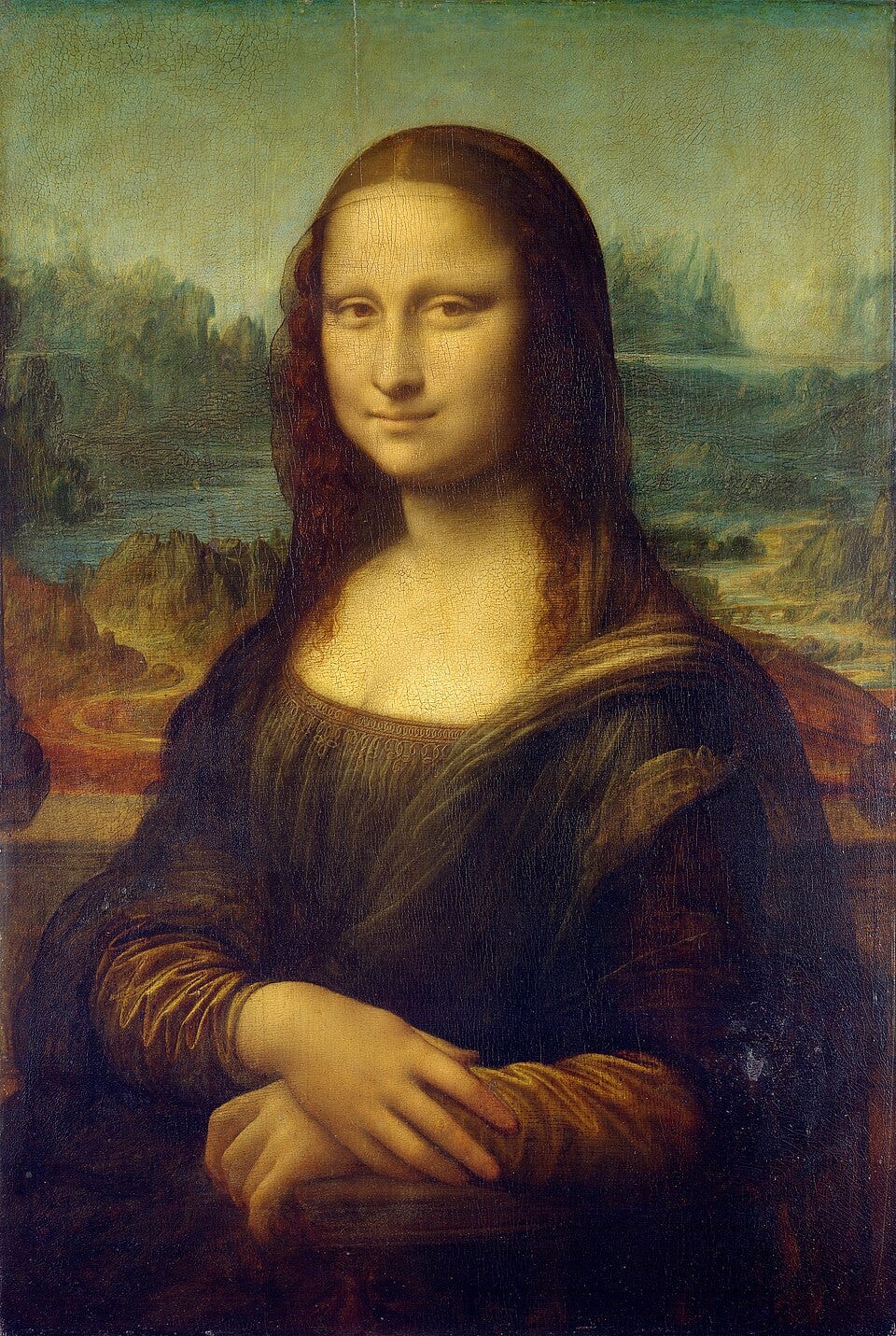

This ensured that art which rose to the peaks of culture was naturally a product of traditional education and reverence for history. Intentionality ruled. Forms and lighting were captured meticulously in studio settings. Anatomy was studied in its gruesome detail.

What is often overlooked is that these were all ancillary to a psychological end. A successful artwork’s purpose was to shape societal tastes through mimesis, teaching people to value whatever the patron or academy valued, and denigrate that which they condemned. If a piece coincided with the authoritative valuations—including aesthetic preferences—it was considered “objectively good” and little more needed to be said on the matter.

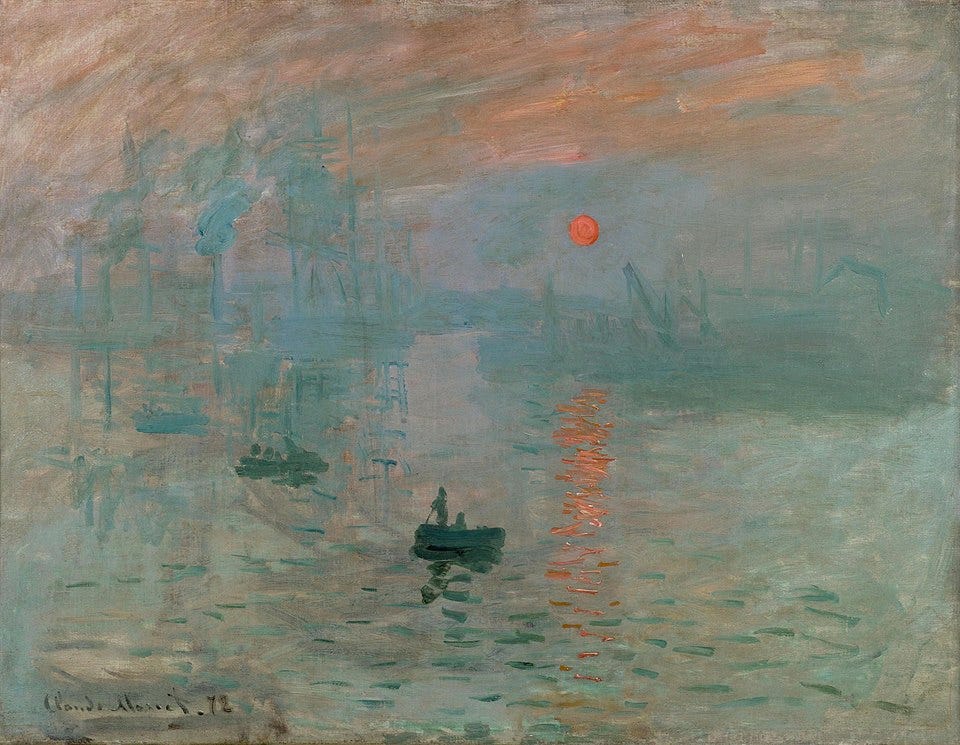

However, it was this belief in “objectivity” as a most holy relic which made society complacent. One thought that by adhering to it as the highest principle, one would naturally stave off all competition. This was not the case. Indeed, the impressionists overthrew the hegemony of the aforementioned Académie des Beaux-Arts simply by placing themselves in contradistinction to it; impressionists as the freedom-loving, revolutionary underdogs, against the pretentious dogmatism of the academy.

To understand why objectivity failed to carry the weight of culture, one need only examine it as a concept, detached from metaphysical prejudices. Objectivity is a word always contingent on arbitrary measures: realism, drama, beauty or even geometric qualities like conformity to the golden mean. Regardless of the technological capacity to measure any given aspect of a thing, there is always a subjectivity in deciding which of its qualities are valuable. In short, “objectivity” only masks instability and perspective, rather than solving them.

Those under the umbrella term of “post-modernism” were among the only people willing to confront this weakness. Some took advantage of the overreliance on “objectivity,” introducing their own systems in its place. They aimed to pivot culture into the realm of experimental and perspectival value systems, citing with great frequency the spirit of liberation for their goal. It is clear that there were both beneficial and harmful downstream effects of their philosophies.

One of these harmful effects, as I see it, is the propagation of modern abstract art. This art can generally be described as spontaneous and interpretive by design; a spasm of chaos, a minimalist design, or inversely, a blank canvas. This art burdens the audience with a project of free-association, acting like a broken mirror for the psyche.

As regrettable as one may find this state of the creative industry, there is still no objective basis to call it “worse” than what came before. Only “less structured,” “less dramatic,” “less conformant to normativity.”

Now, it may still be unclear why I have spent so much time exploring the subject of artisanal crafts and art, given the sweeping title of this essay. The reason is that modern art lies at the intersection where traditional and progressive worldviews collide in their most superficial manifestation, and therefore provides the most revealing insights about their dynamics. By using it as a case study for these worldviews, one can draw out their flaws, and their merits, understanding how the former allowed and the latter encouraged mediocrity to gain ground.

The strength of traditionalists, arising from unshakeable resolve, is their ability to assert value: a “yes” to this, and a “no” to that. When something appears to demonstrate value, they hold onto it. However they are too timid. They always feel the need to back up their assessments with “objective” or “transcendent” values. This is a self-imposed limitation, which relies solely on the sustained, universal belief in these concepts.

The strength of progressives, arising from unbounded adaptability, is their ability to adopt multiple perspectives and bolster critiques with dizzying scholasticism. However, they know not how first to serve and to be an apprentice, for they have escaped from the tempering fires of tradition. They are far too undisciplined to enjoy their own freedom, and so they oscillate unwittingly between destruction and happy accidents.

In my view, it is now necessary for all to abandon the language of “objectivity,” recognising that one’s values lie at the bedrock of the psyche, and one can dig no deeper to justify them. This venture is admittedly perilous. One must also remain disciplined and studied in the art of discernment, knowing when to strike out, when to defend, and when to rest. With this, the ability to deal with conflict becomes second-nature—even desirable.

Many of the symptoms of modernity arise from the venom and bile of two major forces who are averse to conflict, yet compelled to engage in it. Each sees the other as the source of their ills and evils, and therefore concludes that their enemy is corrupted in spirit. They even refuse to speak the same language. But what if each should learn to enjoy the competition, and even trade advice as a token of good faith? What if they, like the ancient Greeks, should wish that they had a stronger enemy, in order to test their own might? Then they may finally realise just how productive their relationship can become.

Great article. Thank you.

I must confess 'modern abstract art' has always been my favorite to create and observe, due to it's power to bypass rational sense making and communicate feeling far more directly than a literal pictorial depiction ever could. But I see that most of it is undoubtedly 'fake' in a disingenuous way - an 'easy option', more like a painting by numbers than heartfelt art.

Anyone who has truly tried to produce abstract art knows that it is not an easy task - in figurative work flaws are easy to spot and correct. When working in the realm of abstract feelings and emotion the flaws and the corrections are far more difficult to pin down. There is no obvious guide apart from ones inner vison. One can spend hours seeking a resolve, reach it, and still not really know 'why' it works - it just does!